Rolv Lorentz Muri

b. 1921 – d. 1992

Born in Ålesund and grew up in Gjøvik. During the Second World War, he lived with his uncle Andreas at Auflem in Olden, in order to evade forced Nazi labour. Studied at the Norwegian Academy of Fine Arts in Oslo from 1946-1948. After further training, Muri married the Danish artist Helga Brøchner-Kristiansen, whom he had met in Copenhagen in 1946. They took over the family farm at Auflem, where they raised cows, sheep, pigs, chickens and horses, as well as growing fruit.

Throughout the 1960s, Muri represented his home country in two major official Norwegian exhibitions abroad. He was included in the Vestland Exhibition thirteen times, and at the Autumn Exhibition five times. He was also awarded a three-year working stipend. This allowed him to prepare for his first solo exhibition in 1969 – 25 years after his first exhibition. In addition, some of his work was bought by the National Gallery. In 1977, Muri was one of the first artists to be granted a guaranteed working income by the government.

This website is presenting the painter Rolv Lorentz Muri from Olden. As a child I grew up in the same region, actually the neighbouring village Stryn. I came across a painting by Muri at the age of 15 at the school I was studying at. The painting was titled “Nattlig dialog” or “Dialogue in the night” (1977). This image has never left my mind. Now, after a 10 year long process, the book “From Olden to Paris” is now being released on various books stores in Nordfjord. The manuscript was made by the fabulous writer Ove Eide. In December 2021 we celebrated the 100 anniversary since his birthday with the release of “Murimorphosis” on Arve Music.

Kunstnar og bonde by Ove Eide

Rolv Muri grew up in Gjøvik, but moved back to Ålesund in 1937. He attended middle school and then started working for the Post Office, where he both received an education and found employment. Professionally, it seemed that he was going to follow in his father’s footsteps. However, he wasn’t particularly happy working at the Post Office. His sister, Liv Wartdal, clearly remembered that he grew tired of it: “He had to do something more than stamp letters,” she once said. In a retrospective in 1974, after he had been a farmer for over 25 years, he said:

“(I) sat on the office chair from 9 to 4 for a short time in my youth. I’m glad I switched to plowing fields, spreading manure, and planting potatoes.” (Morgenavisen, March 15, 1974)

Liv Wartdal has mentioned that there was little talk of visual art in the family home, but their mother had artistic tendencies, which she expressed through sewing. The family had a great interest in music, with a lot of singing. Rolv himself played the violin, his brother Elling did too, while Asbjørn played the accordion. During the war, Rolv Muri lived in Olden, and was often involved in playing music for dancing at the youth house Aldaheim, along with Johannes Sunde on accordion and Martin Bakkeli on guitar. His sister does not remember Rolv talking about dreams of becoming an artist, but evidence that he was a little more than usually interested in drawing can be found in A-magasinet, Aftenposten, in 1929. They had a section where children could send in contributions, and in the issue from June 1, we read that one of those who submitted a drawing was Rolv Muri. The drawing was not published, but it must have been encouraging to see his name in a major newspaper. The list of submitted drawings in this issue contains 41 names, all children between the ages of 6 and 12.

WAR YEARS IN OLDEN (1940–1945) by Ove Eide

When the war began in May 1940, Rolv Muri was a postal clerk, working in Fredrikstad. He had moved there from Ålesund in January 1940 and stayed in the city until October. At that point, he applied to return to Ålesund and was employed at the post office there until the New Year. The documents show that he requested to go back to Ålesund because of his health, though no specific details are provided about what troubled him: “It is sad that you are leaving us, Muri, but everyone must bow to illness,” says a letter from the Post Office in Fredrikstad (dated October 10, 1940). At the turn of the year, he applied for a discharge from the postal service and his request was granted on January 10, 1941.

From Ålesund, he then moved to Nordfjord, and he is registered at the Innvik Police Station with the address Olden from January 30, 1941.

But it seems there was more than just health problems that led him to settle in Olden. He later mentioned that he moved from Ålesund to Olden to escape the Nazi Labor Service (AT). This service had been introduced as a voluntary service by the Administrative Council in the summer of 1940 and made mandatory for men of conscription age by Nasjonal Samling (the National Gathering) from the fall of 1940.

During the rest of World War II, Rolv Muri lived and worked on his uncle’s farm in Auflem. Evidence of his commitment to farm work can be found in a “Fruit Packager Certificate” from the Norwegian Horticultural Society. Muri attended a course in sorting, packing, and labeling fruit at Rake in Loen in October 1941 and received a certificate valid for five years.

Olden during the war was a quiet place. The people in the village noticed little of the military actions, even though the nearest German garrison was located in Stryn, less than 20 km away. The local cultural life flourished, with significant activity in song and music: The village had three choirs—a mixed choir, a male choir, and a women’s choir.

Nordfjord had scarcely anything that could be called an active artistic community during the interwar period, although the area had many amateur artists. But there was one exception, right in Olden.

In 1913, the American multimillionaire William Henry Singer (1868-1943) and his wife Anna Spencer (née Brugh, 1878-1962) came to Olden to engage in sport fishing in the Olde River, which was known for its excellent salmon fishing. Singer was from Pittsburgh, USA, and was an heir to one of the largest steel companies in the country. However, his life path did not lead to industry and business. Here is the translation of the text into English:

For he was interested in art and was himself a skilled painter. After having two of his paintings accepted for an art exhibition in 1899, he chose to forgo the right to take over the family business. Instead, he wanted to focus on art. A great help in this pursuit was the large financial inheritance he received, which is believed to have been worth several tens of millions of kroner. (Møller 1999, p. 24)

Singer built a studio in Olden in 1914, and in 1921, the villa Dalheim was completed, later known as Singerheim. The couple lived there annually from April to September. For the rest of the year, they lived in Laren, Holland. Singer was socially engaged and donated large sums to charity, both in Olden and elsewhere in Nordfjord, including the construction of the Olden-Innvik road and the establishment of a hospital in Nordfjord. He also gave an interest-free loan to establish Firda Gymnasium in Sandane.

Composer Sparre Olsen (1903–1984) was a friend of Singer and lived at Dalheim for several years during the war. Both he and his wife Edith contributed to the musical life in the village while they lived there: She gave piano lessons, and he arranged songs for the choirs and provided guidance to the conductors. Sparre Olsen composed the melody for “Olden” by Olav Skarstein, a song that has been widely used in the local community. Skarstein was from Olden, a priest, hymn writer, and versatile cultural worker. He helped start the Christian daily newspaper Vårt Land in 1945 and was its first editorial secretary.

Singer was an avid art collector, and at Dalheim, they had a large art collection. As an artist, Singer was an Impressionist, a “painter of impressions,” with a great appreciation for, among others, Monet. For the Impressionists, it wasn’t the landscape itself that was interesting, but their own experience of light, weather, and mood in the moment they wished to capture on canvas. Singer’s subjects were landscapes, often from Olden. In his paintings with Olden motifs, he attempted to capture his experience of light and atmosphere in a West Norwegian landscape, at a specific place and time. The artist Singer is represented in several art museums and galleries in Europe and the United States.

The widow Anna Singer bequeathed 700 items from Singerheimen to the West Norwegian Museum of Decorative Art in Bergen. This “Singer Collection,” which includes both large and small objects, from furniture to paintings and lamps, is now part of the KODE Art Museum.

One of those who drew inspiration and knowledge from Singer was the grandfather Ingebrikt Beinnes (1885–1971), who apprenticed with the American in the 1920s: “In the artist environment at Dalheim, he got to see and experience much art, meet other artists, and gain new knowledge.”

From 1940 to 1960, an art school was held during the summer at Singerheimen, led by one of Singer’s friends, the Dutch artist Jaap Dooijeward. This was the first art school in Sogn and Fjordane. Talented young people from all over the country came here to receive training and guidance. They rented rooms in the village’s farms, and Dooijeward went from house to house to teach the students. The students created still lifes and copied old classical masters, such as Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein. Among the students, who often attended here for several summers in a row, were Jenfrid Hermansen Heienberg, Harry Botn, Elling Vanberg, Alf Apelseth (who was a student at the Academy of Art in Oslo at the same time as Muri), Kaare Sunde, and Reidar Letrud.

Rolv Muri was not a student of Dooijeward, and in a handwritten note that he likely wrote as preparation for an interview in the late 1960s, he mentions the environment around Singerheimen during the war: “But personally, I had no connection to this environment.”

However, it is difficult to imagine that the art-interested youth wouldn’t have received influences from this rich artistic community of young people around his own age. He has himself mentioned that it was during the war years in Olden that his interest in art was truly awakened (Braadland 1991, p. 19).

For the most part, he probably kept to himself, but it is reasonable to believe that he may have had some contact with other art-interested people in the village.

FARMER AND ARTIST (1948–1966) by Ove Eide

In 1948, Rolv Muri took over the farm where he had lived during the war years. He married in Denmark in May of the same year, and the newlyweds attempted to make a living from art. In his own words, 30 years later: “Took over the family farm in Olden in 1948 after marrying in Denmark and failed attempts to survive as an artist in Kh (=Copenhagen).” (in a draft for the application for the State Guarantee Income in 1977)

His uncle, Andreas Monsson Auflem (1884–1953, half-brother of his mother), and his wife Didrikka (née Skarstein, 1883–1942) had no children, and Rolv and Helga Muri seized the opportunity when they were offered to become farmers:

“It was an uncle who owned the farm, he became ill, and I was offered to take over. It was on an autumn day when we arrived in Olden, my wife and I, straight from Copenhagen. Up on the mountainside, a light flickered in the darkness.

– That must be it, I said. – It looks a bit lonely. We didn’t know what we were doing, but we were nostalgic, thirty years before it was invented.”

(Sunnmørsposten, August 27, 1976)

The farm he took over is farm number 3 at Auflem. In the first years, the Muri couple focused on full-scale farming, with cows, sheep, pigs, chickens, horses, and fruit cultivation. However, around 1970, they scaled down the operations to sheep and vegetable farming. Muri tried to pack away the land but was unsuccessful.

He always felt a strong sense of duty and responsibility to maintain the farm. The family had lived there since the 1500s. Therefore, they remained on the farm.

The Muri couple moved from the big city to the countryside before it became a political goal to decentralize art and cultural life in the 1970s. 25 years after they arrived in Olden, the slogan “art should reach the people” became popular, and it was made economically feasible to make a living as an artist even in rural areas. The 1970s became a decade of increasing funding for cultural purposes, with a specific parliamentary report on cultural policy (1974). The “Artist Action 1974” was a cross-disciplinary collaboration where artists demanded increased use of art, guaranteed minimum income, and fair payment for the use of artworks. Rolv Muri benefited from these initiatives.

Choosing Olden and the life of a farmer instead of being an artist in a big city was a decision that Muri justified both with a sense of family duty and obligation—not with political arguments. It was a responsibility he had to take, as part of a long family line. But the choice was likely also connected to the highly uncertain path of pursuing a career as an artist in the immediate postwar period. Their finances were poor, but with the farm, they gained both a place to live and a basic income. The first years were tough: Rolv was in poor health, and much of the work fell on his wife, Helga.

The transition to farming was a harder struggle than they had anticipated:

“I put the brushes completely aside; we had to concentrate on the farm in order to survive. But after five or six years, I started again. I would walk around and see everything around me that begged to be treated artistically. I painted in stages, between tasks, and since then, I’ve taken it steadily. It was a great stimulus when I joined the UKS.”

(Sunnmørsposten, November 13, 1965)

(UKS = Young Artists’ Society)

There was little time for art, but he would not trade rural life for city life:

“We chose this life. Look how breathtakingly beautiful it is here! I always thought of the countryside when I lived in the city. Longed to return to the rocks and grass. It must be in my blood, living like this on a shelf. Both sides of my family come from this steep slope.”

(Dagbladet, July 30, 1966)

Neighbors have put up a road sign to honor the artist.

Photo 2023: Håvard Eide

Both Rolv and Helga missed contact with the art community. It was far—and expensive—to travel, both to Bergen and Oslo. And neither could be away at the same time, as the animals had to be cared for. But he admitted that it would have been nice to live in Oslo for a few months now and then, to attend exhibitions and galleries in peace.

(Dagbladet, July 30, 1966)

Muri became a member of the Young Artists’ Society (UKS) in 1956 and received the UKS work scholarship in 1957. UKS was founded in 1921 and serves as both a professional association, exhibition organizer, and a social and professional meeting place for artists. UKS has focused on contemporary art and been a pathbreaker for experimentation, renewal, and debates on art, ideology, and the working conditions of artists. It has often been in clear opposition to established art. From 1959 to 1989, UKS held an annual spring exhibition, in direct opposition to the established Autumn Exhibition. (For the history of UKS, see Schønsby and Haugen 2021).

In 1959, Rolv Muri also received a scholarship from the Chr. Lorck Schive Foundation. This is named after Christian Lorck Schive (1803–1879), the hospital director in Trondheim, and was based on income from properties in the city. Both scholarships were important to Muri, both financially and as inspiration for further work. In both awards, there was also recognition of him as a serious artist.

MY TRUMPET IS MY PAINTBRUSH by Arve Henriksen

I remember very clearly that when I was a child I was constantly aware of sounds, colours, structures and nuances in nature all around me. When I climbed trees I could feel the texture of the bark pressing against my fingertips. The strong scent of heather and marsh would linger in my nose when we played in the woods from early morning to late evening. Wind, waterfalls and streams all had their different orchestrations and sound colours. Birdsong emphasized the seasons, and the cuckoo lent a perspective of depth to the forest world.

From my bedroom window at Kreklingen in Stryn I could look straight across at Mount Årheimsfjellet towering 1000 metres above sea level, and in a way it became my canvas. The mountain had so much to offer, from majestic calm to dramatic episodes such as avalanches and rock falls. Every day I would observe the gradual erosion and changing colours of the mountainside, and there was always something new to see. On wet autumn days there would be a change of scene as dozens of new rivulets and streams of varying sizes appeared and the last yellow leaves were washed away. On heavy, grey November days, drifting snow showers high up heralded the arrival of winter, descending lower and lower down the mountainside as the month progressed. From December until well into January the rocky colossus blocked out the sun. The structures in the mountainside – nature’s skin, as I called it – changed as the sun went on its course. It was nature’s movie theatre, and I would sit there and be amazed at the dancing frost mist on the river and the ever-changing patterns on the surface of the fjord.

My observations would sometimes gather in a strange mixture of sounds, colours and emotions, creating a kind of peculiar “pressure” inside me. This yearning or pressure I subsequently learned to recognize as my artistic drive. It is a combination of my emotions and artistic ideas urging to be expressed in sound, in writing as stories and poetry, or in paint on canvas.

I have often thought that I quite literally breathe life into my artistic ideas, and that my trumpet is my paintbrush. The air in front of me and around me is my own mobile canvas, while at the same time I can paint directly, as it were, on the listeners’ canvases.

Over the past 10 years I have often been inspired by Muri’s art. I noticed that Sverre Fehn’s use of contrast in his design for the Glacier Museum in Fjærland is similar to Muri’s use of contrast in his paintings. A distinct and clear form which might be seen as a provocation, but at the same time evokes a vital sense of wonderment in the observer who is open to the experience.

The process of working on the book “From Olden to Paris” has made very clear to me a quality shared by all the local artists I have focused on – Rolv Muri, Elling Vanberg, Oddleiv Apneseth and Kjartan Hatløy – namely their talent for observation which manifests itself in profound character, strength, and form in their art. The way in which Muri observed and interpreted nature, and the way in which this was translated in his art, has affirmed my belief that my own observations reinforce my own artistic expression. I realize too that this has led to me becoming more confident and better aware of choices I make in my music.

I have discovered many similarities between creating a musical composition and painting a picture, or even writing poetry. The shaping of a note on the trumpet is just as nuanced as the process of mixing the right shade of colour for the brush to express on canvas. Breath pressure, attack, duration, hardness, release, and choice of pitch are ingredients in my palette. Explaining my need to express myself through art is something I have put behind me. Now I simply enjoy giving myself over to it, being creative and discovering new sounds and new paths to tread; I am grateful for and delighted by the inspiration I find in others.

This mountain was my canvas. If you climb it, your perspective changes. Little did I know that Muri and Vanberg were there on the other side of Mount Årheimsfjellet doing their own thing. Now I know more and am eternally grateful for them showing me nature’s hieroglyphics and my undiscovered, inner cathedral.

– by Arve Henriksen / translated by Andrew Smith

———————————————————————–

Exhibition in Førde, Norway 3rd of November 2023 – 7th of April 2024:

https://misf.no/en/art-museum/events/rolv-muri-i-paint-with-dirt-under-my-fingernails

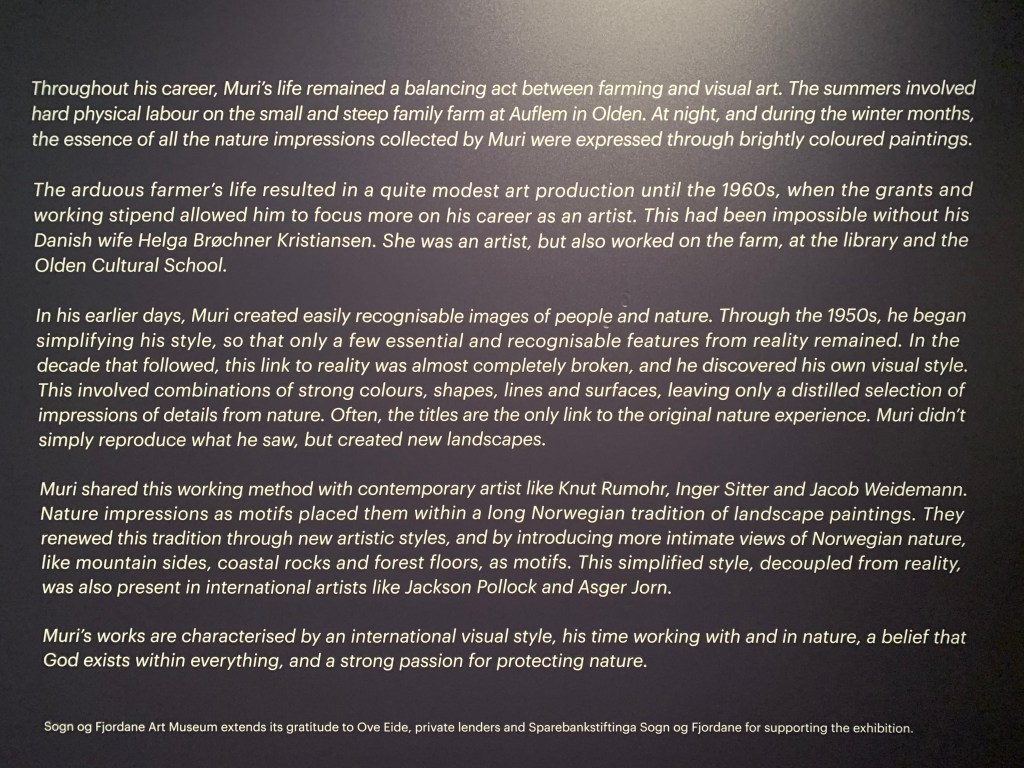

Text presented in the exhibition in Førde:

https://wordpress.com/post/rolvlorentzmuri.com/627

Liner note Murimorphosis (digital release on Arve Music) :

“In the early 1980s I was a pupil at Stryn junior high school. There I encountered Muri’s art for the first time, in the form of his painting “Nattlig dialog” (‘Nocturnal Dialogue’) (1977). It is also where I had my first encounter with the poet Elling Vanberg. He visited one of our Norwegian classes at the invitation of our teacher Magne Drageset. The poetry we heard that day imprinted itself on my brain as something very special. And it has had artistic consequences for me in my creative career: Ellivan’s poetry was part of “Farande Bilete” (‘Travelling Picture’), a work commissioned for the Bale Jazz festival in Balestrand in 1997, and in 2008 when I released the poetry phonogram “Ellivan” (NorCD). And now, nearly 40 years later, the way that first encounter imprinted itself on me has encouraged me to initiate an art book about Muri, and to make this recording. “Murimorphosis” is to be taken as a free and independent journey through a variety of moods, while at the same time in its own way inspired by that unique artist from Olden.”

Arve Henriksen (Translated by Andrew Smith)

For questions and further information, please contact Arve Henriksen: arve(at)arvemariamusic.com